Why Albanians vote for Rama, or when elections are not enough to change power

In a country burdened by accusations of corruption, agile authoritarianism, institutional capture, and failures in key sectors like healthcare, justice, and education, the continuous electoral victory of Edi Rama and the Socialist Party appears to be a democratic paradox.

But is it truly a paradox?

Not necessarily.

What is happening in Albania is a typical manifestation of expanded electoral dominance by a leader who deeply understands that in fragile democracies, power is not won merely through ideas and programs, but above all through control of information, management of collective emotions, and systematic use of public resources as political tools.

The Albanian citizen votes, but in a controlled environment, where alternatives are weakened, fear of change is strong, and the institutional system is so subordinated to the executive power that even hopes for justice and equality seem futile. In this context, voting is no longer a tool for changing power, but often just a ritual act, devoid of substantial weight.

The “Five Engines” that sustain Rama’s Power

To understand why Edi Rama continues to maintain stable political dominance in Albania, it is not enough to look at the electoral result. We must analyze the specific mechanisms that feed and regenerate this power, regardless of waves of discontent, social crises, or public policy failures.

This long hold on power is not merely the result of personal charisma or political luck. It is built on an interwoven architecture of control, functioning through centralized communication, smart clientelism, fear of alternatives, institutional capture, and a frightening use of stability as a persuasive tool. These are, essentially, the five engines sustaining Rama’s electoral regime—a regime that operates within a democratic form, but outside its essence.

Below is an analysis of these five pillars, which make power not only durable but also resilient to criticism and scandal.

1. Total Communication – the leader as a “national screenwriter”

Edi Rama has built not just a government, but a communication regime, where every message, crisis, success, or failure passes through an aesthetic, emotional, and performative filter. This performative leadership finds parallels in Mateusz Morawiecki in Poland (with a focus on “family and identity”) and more extremely in Orbán in Hungary, who uses the media to create an alternative reality.

2. Opposition as a threat to stability, not as a governing alternative

In a consolidated democracy, the opposition is a dialogue partner. In Albania, it is treated and perceived as a threat to stability. When the opposition is represented by worn-out figures or past-laden narratives (Berisha, Meta), Rama appears by default as the “more manageable evil.”

This strategy mirrors that of Janez Janša in Slovenia, who mobilized fear of a return to “communism” or “liberal chaos” to stay in power.

3. Power as a tool of loyalty

In the absence of a functioning social state, support for citizens turns into personalized clientelism: jobs, legalization papers, economic aid, short-term employment around elections. This is the Albanian version of the “party-state” model. A close parallel can be found in Bulgaria, where Boyko Borisov built a system where power was not only political, but also economic and social. Every vote for the ruling party translated into a concrete material promise, not an ideological one.

4. The symbolism of stability vs. fear of chaos

Many Albanians, exhausted by the uncertainty of transition, have turned stability into a politically self-justifying value. It’s not that they are satisfied with Rama, but they believe that any alternative would bring more instability.

This survival psychology mirrors the reality in Southern Italy, where voters often choose dominant local leaders not because they are the best, but because they are the most predictable and preserve the status quo.

5. Institutions as democratic decor, not power checks

The capture of institutions from independent ones to public administration has significantly diminished the checks-and-balances function of democracy. Elections alone are not sufficient to judge the health of a democracy. Hybrid democracies, like Albania, are the clearest examples of this.

Rama is not an exception, but part of a wider model.

The phenomenon of a prolonged leadership dominance in hybrid democracies is not uniquely Albanian. It is part of a broader trend that has emerged in several Eastern and Southern European countries, where the formal institutional shape of democracy is maintained, but its content is transformed into a system of controlled representation, weakened competition, and state capture.

In this context, Edi Rama is not a Balkan anomaly, but a local variation of a structured political model, functioning based on five common elements.

- In Hungary, Viktor Orbán institutionalized a model where control over public narrative is total, through media capture and the use of state budgets as loyalty rewards. He labels any challenge to power as a national threat—a tactic echoed in how Rama treats the opposition and critics.

- In Poland, the ruling party (PiS) under Morawiecki uses a rhetoric of fear of value change, portraying the opposition as a danger to stability, family, and moral order. This “framing” strategy makes the ruling power seem like the guardian of normalcy—a tactic Rama uses to present himself as the only force that can “protect Albania from political chaos.”

- In Serbia, Aleksandar Vučić has built a system of centralized and orchestrated media, channeling all public debate in favor of the government. Faced with a fragmented and discredited opposition, Vučić appears as the rational and inevitable leader. Similarly, in Albania, public debate is controlled, oscillating between propaganda and discrediting all alternatives.

- In Bulgaria, Boyko Borisov represents the classical model of personalized clientelism, where support for the government is built through direct relations with citizens, selective use of public funds, and a weak institutional apparatus that fails to provide oversight and accountability. This model closely resembles the practices of Albania’s Socialist Party.

- Finally, Southern Italy offers a revealing case, where local power structures, not the central government, produce this model. Citizens vote not out of belief in political alternatives, but to avoid losing “guarantees” tied to local leaders. This mentality is strongly reflected in Albania, where perceived stability outweighs change, and the leader is seen as guarantor of order, even if that order is unjust.

When democracy dies slowly.

Continuous voting for Rama is not a sign that Albanians are naïve or uninformed. On the contrary, it reflects the distorted conditions of democratic competition and a sophisticated strategy of retaining power through control, fear, symbolism, and the weakness of alternatives.

At the end of the day, this situation raises a bigger question:Is democracy merely an electoral process, or a system with real accountability mechanisms?

This is not a uniquely Albanian phenomenon. In Hungary, Poland, Serbia, Bulgaria, and even parts of Southern Italy, we’ve seen how clever political leaders have built systems that look like democracies, but function as power monopolies, keeping society attached to the idea of false stability.

But what makes Albania unique is the normalization of this reality.

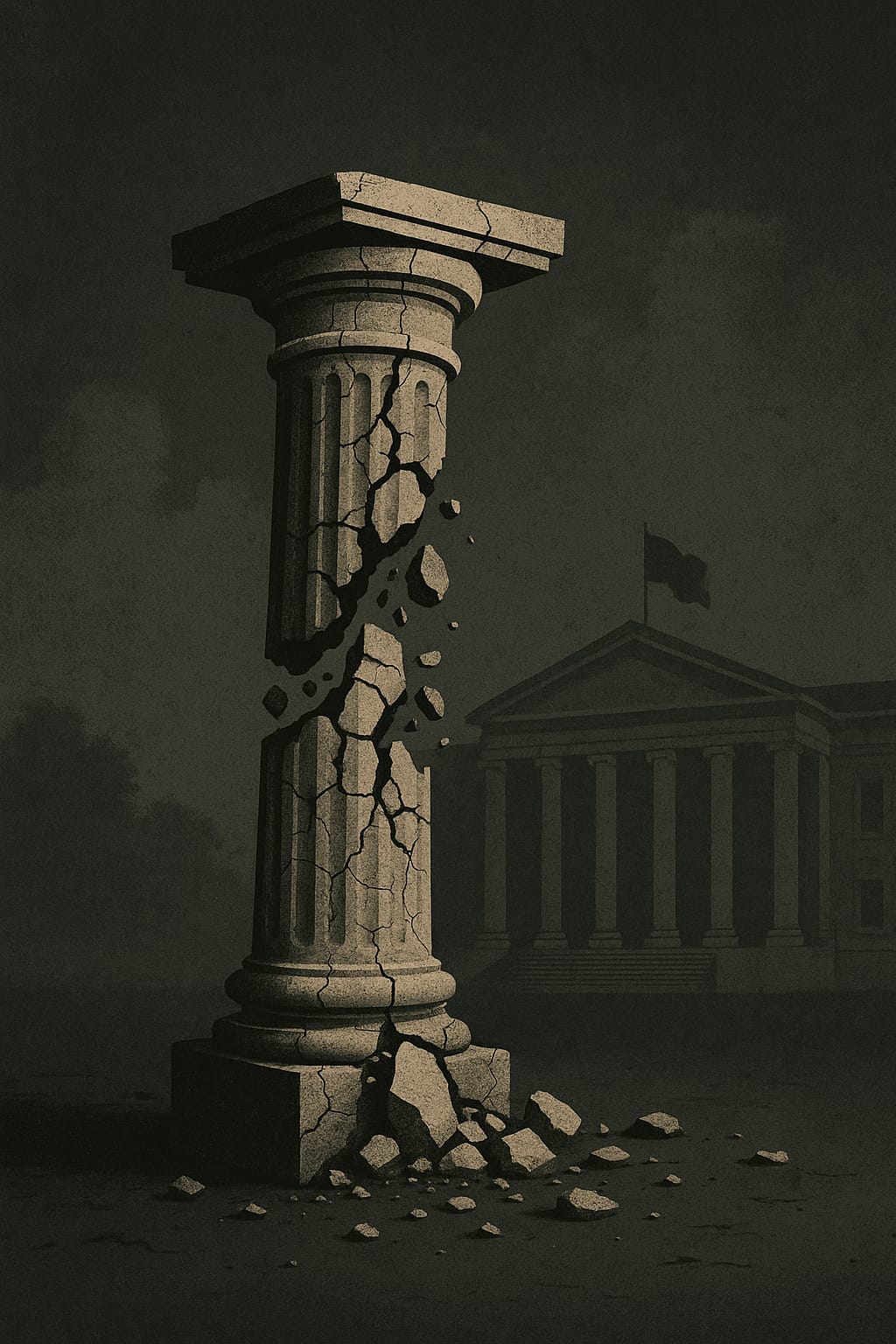

The fact that most citizens have accepted that “this is how things are and always will be”, or this “collective fatigue of hope,” is in itself the clearest sign that democracy is not collapsing all at once, but is slowly decomposing—like a body losing its vitality with a long, unheard sigh.

And yet, history shows that even when the lights go out, a single spark is enough to reignite them.

And the spark isn’t always political!Sometimes it arises from culture, sometimes from the younger generations, and sometimes from crises that expose the system’s lies.So, the real question is not “is democracy dying?”, but:“Who will dare to awaken it from its coma?”